by V. Ramnarayan

What is the Musiri bani? Listen to what his star disciple Suguna Purushothaman had to say about him during Musiri Margam, an illuminating tribute she paid to his memory—during the late evening of her own life.

“The years I spent learning music from Musiri Subramania Iyer marked a golden period of my life,” she told the small audience that had gathered to listen to her that afternoon. “While attending one of his concerts, you forgot after the first few moments that he was singing or even that you were listening, so deep was the bliss of complete absorption in the music.”

Suguna was fond of demonstrating to friends and rasikas the Musiri way of niraval or swaram singing, with special emphasis on niraval, on how he stressed the importance of getting the lyric right, of choosing the best possible place in the song to do niraval, of how vital the meaning of the lyric was to this choice.

Rather early in the lecture-concert, she presented Musiri’s famous Mukhari and Enta ninne in that raga, but later, she also offered the delights of rare raga Kokilavarali, in which, according to her, Musiri revelled. She offered a sensitive exposition of Khamas, and a wonderful Sama kriti Varuvaro by Gopalakrishna Bharati.

Suguna repeatedly spoke of Musiri’s bhakti for Tyagaraja, taking listeners on a glimpse of the utsava sampradaya in the process. Her own bhakti for Musiri was much in evidence. She was able to laugh at her own and her peers’ inadequacies and the great patience the guru showed them. Never one to utter a sharp word, Musiri restricted criticism to smiling admonition of the multitude of angularities in the students’ interpretation of his lessons (Ellame konal).No note-taking was allowed in class, and tape recorders were a rarity (“TK Govinda Rao flashed one around after a trip to Singapore”; this with a mischievous twinkle in her eye). “You repeated after the guru as he took you through whole kritis in each class until you got it right.” Musiri was a caring if strict teacher.

If niraval was Musiri’s speciality, so was his own unique brand of swara prastara, with short phrases falling seamlessly in place with the raga bhava fully intact.

“The importance of niraval singing and its intricacies in this bani are well known,” said Brindha Manickavasakan, a senior student of Suguna Varadachari, herself a prime disciple of Musiri and an accomplished votary of the bani. “When we all sang niraval in class, Mami’s approach to that—of singing separate niraval rounds before each one of us took our turn— is really special. Mami said this was something Musiri always did—as opposed to the method of the guru singing one round and then each student taking a turn one after the other. It felt personal, it was a unique bonding experience in itself.”

“With a vibrant voice, and open throated singing, Musiri also stressed the importance of vallinam mellinam modulation in music. Suguna Mami has also taught us that precious quality. I think it teaches us sensitivity and awareness of what’s happening in the music.”

The emotion-filled rendering of songs was indeed Musiri’s forte. Suguna Varadachari listed her favourite Musiri songs in an interview with Vaak magazine. These included Endu Daginado (Todi), Na Morala (Devagandhari), Entaninne (Mukhari), Rama Rama Gunaseema (Simhendramadhyamam), Devi Jagajjanani (Sankarabharanam), Janani Pahi (Suddha Saveri), Kavadi Chindu, Mela Ragamalika, Kana Kan Ayiram (Neelambari), Amba Nadu (Todi), and Paruvam Parkam (Dhanyasi). She also marvelled at the preponderance of bhava in the songs he tuned. “Many Swathi Tirunal songs he tuned bore the indelible Musiri stamp in this regard,” she said. Examples are Devi Jagajjanani, Sri Kumara, Anjaneya Raghurama and Palaya Raghunayaka.”

Music historian V Sriram paid this emotional tribute to Musiri and his music:

“It is not often the fortune of an artiste to draw tears from listeners’ eyes, even as he or she performs. But to endow even replays and recordings with such an ability, is almost an impossibility. Musiri … had perfected this art to such an extent that… his feats in bhava, especially in niraval, have never been matched.

“The voice was high for a man. In his youth, it was even higher (F Sharp) and as he aged, it did drop to D Sharp, but the high voice, in complete unison with the drone of the tanpura, created a mesmeric effect, often likened to a bee flitting about in garden of music in springtime. The body was often frail, but it scaled Himalayan heights when it came to musical tourneys. The combination spelt dignity, a dignity of art, of accomplishment and achievement, from which he never lowered himself.

“Till the mid-forties, he was a busy concert artiste. The great concert Halls of Carnatic Music, such as the 100 pillared hall, Rockfort, Trichy, the Gokhale Hall, Armenian Street, Madras and the Nellai Sangeetha Sabha, echoed to his voice as thousands gathered to hear. It is said that when he rendered Taye Yashoda or Teyilai Tottatile , there would not be a dry eye in the audience. Packed with bhava, he alone amongst his peers had the magic of portraying multiple emotions in a single line of a song, while still remaining within the contours of a raga. Who could forget the way he interpreted the line beginning “gagana” in Nagumomu?”

Musiri was perceived as a highly educated man, with an excellent command of English, a strange but crucial component of the attributes of artists in Anglophile Tamil country. The Musiri aura was completed by his knowledge of literature and world affairs, though he never went to college.

The elite of society from business icons to bureaucrats and litterateurs treated him as their equal, and he never stooped to win patronage, unlike some of his contemporaries and predecessors.

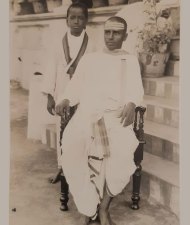

He was born on 9 April 1899, the second child of Sankara Sastry and Seethalakshmi at Bommalapalayam, a village in Tiruchi district.

Sankara Sastry was a Sanskrit pundit and priest. Seethalakshmi died when young Ayya, as Subramaniam was called at home, was still a baby, and elder sister Rajathi had died young, too. His brother was Kuppuswamy. Ayya was only fourteen when he married Nagalakshmi, who was two years younger.

His grand-nephew S. Thyagarajan (who prefers to be called his grandson) remembered Musiri telling him that he stopped school after class four, though his erudition led many to believe he had a college degree. He spoke and wrote excellent Tamil and English taking the trouble to educate himself. He regularly visited friends at the hostel of Tiruchi’s St. Joseph’s College and borrowed books from them. He read Shakespeare and Dickens, and devoured the daily newspaper. Pears Encyclopaedia was his constant companion.

Musiri loved the music of SG Kittappa, the sensational singing star of the Tamil stage. He listened to his magical voice on gramophone records, and often tried to imitate it before an appreciative audience consisting of his hostel friends.

He became a student of S Narayanaswamy Iyer, a brother of the principal of the Maharaja’s College in Pudukotai, to learn Carnatic music from him. He later trained in gurukulavasam with violinist Karur Chinnaswamy Iyah. After a while, the busy concert artist that he was, Chinnaswamy Iyah advised Musiri to move to Madras to learn from TS Sabhesa Iyer, a much respected disciple of Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer. This was in 1920. For nine years, Musiri spent almost all his time in near gurukula vasam with Sabhesa Iyer.

Sabhesa Iyer was a hard taskmaster, but Subramaniam, whom his guru called Mani— was a disciplined disciple. To learn from him, Subramaniam had to walk from Tripllcane to Purasawalkam where his guru lived, and back, since he could not afford the bus fare.

Tutelage under Sabhesa Iyer, who was a brilliant teacher although not a popular performing artist, shaped Subramaniam as a musician with both lakshana and lakshya gyanam, a beautiful marriage of technique and style, grammar and creativity. Sabhesa Iyer later on served the Annamalai University as principal of its music college for many years and brought the institution great fame. Years later, following in his guru’s footsteps, Musiri became the first principal of the Central College of Carnatic Music in Madras, making it into an institution of great excellence. The strongest weapon in Sabhesa Iyer’s musical armoury was his niraval-singing, and unsurprisingly, it was Musiri’s, too.

Subramaniam had already made his concert debut when he was 17. He had sung at a public function and, impressed by his effort, FG Natesa Iyer, a connoisseur and patron of Carnatic music, had presented him with a medal.

His first concert in Madras took place in 1920, a sabha cutcheri in Triplicane. According to Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, the sabha it was that announced the name of the vocalist of the evening as Musiri Subramania Iyer.

Another story has it that he was advertised as Musiri Subramaniam during a concert at Musiri, arranged by his guru Chinnaswami Iyah. Musiri Subramaniam rolls off your tongue so much more easily than Bommalapalayam Subramaniam, doesn’t it?

Musiri established himself rapidly as a promising talent, but his father did not live to see him attain fame. He passed away in 1925. Subramania Iyer’s brother Kuppuswamy also died in 1929. Young Musiri, who had no children of his own, now had to assume the responsibility of providing shelter to his sister-in-law Parvathy, nephews Sankaran and Subramaniam, and niece Meenakshi. Musiri took this responsibility seriously, caring for the nephews and niece with great affection and concern. Their children, including Thyagarajan, became the grandchildren of Musiri and Nagalakshmi.

Musiri earned a substantial income as a musician and recording artist. He could afford to acquire and maintain a series of cars and live in comfort, with dignity.

Musiri’s popular appeal soared with every season, peaking around his tenth year as a concert performer. His accent on bhava, in fact, the spontaneity of his emotional rendering of songs, often brought tears to listeners’ eyes. His trademark offerings included Tyagaraja’s Enta vedukondu (Saraswati Manohari), Nagumomu ganaleni (Abheri), Na moralakimpavemi (Devagandhari), and Pahi Ramachandra Raghava (Yadukulakambhoji); Muthuswami Dikshitar’s Neerajakshi Kamakshi (Hindolam) and Sree Venugopala (Kurinji); Pallavi Gopala Iyer’s Amba naadu vinnapamu (Todi); Anai- Ayya’s Amba nannu brovavey (Todi); Gopalakishna Bharati’s Tiruvadi Saranam (Kambhoji); Oothukadu Venkata Kavi’s Taye Yasoda (Todi); Neelakantha Sivan’s Enraiku Siva kripai varumo (Mukhari); and Viritta senchadai aada (ragamalika viruttam). “Clear diction and sensitive modulation of voice in an extra-slow speed” set his singing style apart, according to Sruti magazine.

His royalty earnings from his 78 rpm discs brought him prosperity. Quite apart from the famous songs above, they also included songs of social protest like Teyilai thottathiley, while other songs like Tiruvadi saranam and Nagumomu were best-sellers. Grandson Thyagarajan was pleasantly surprised when he saw in a cinema theatre that the opening credits of an MGR movie were accompanied by the soundtrack of Teyilai thottathile. Bemused, he thought it was a mistake committed by the projection room, only to realise that the film was about the struggles of Tamil tea estate workers in Ceylon, now Sri Lanka.

Musiri had the best of the violinists, and mridangam and other percussion artists accompany him. The violinists included Papa KS Venkataramiah, Tiruvalangadu Sundaresa Iyer, Kumbakonam Rajamanickam Pillai and Mysore T Chowdiah, who were reportedly his favourites; as well as Karur Chinnaswamy Iyah, Madras Balakrishna Iyer, Tiruparkadal Srinivasa Iyengar, Varahur Muthuswamy Iyer, Marungapuri Gopalakrishna Iyer RK Venkatarama Sastry and, later, Mayavaram Govindaraja Pillai. Among his younger violin accompanists were TN Krishnan and Lalgudi G Jayaraman.

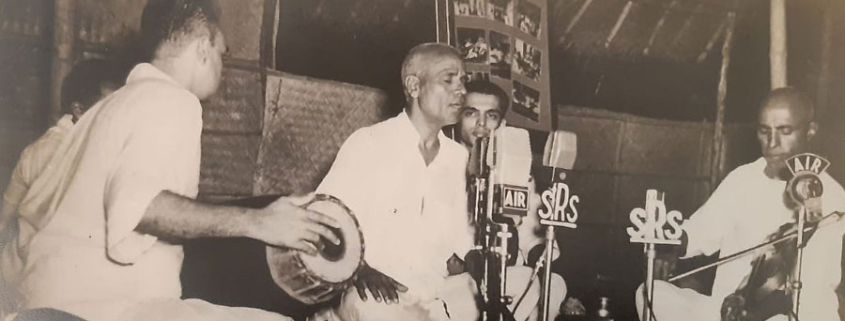

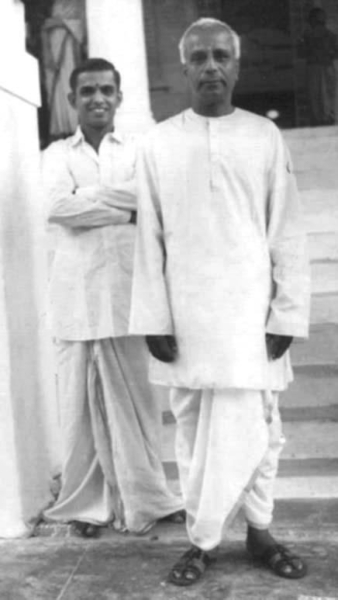

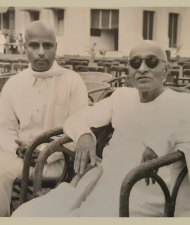

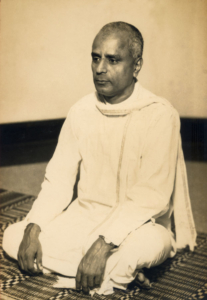

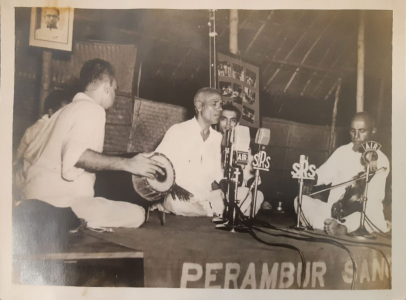

Musiri Subramania Iyer with RK Venkatrama Sastry, Nagercoil Ganesa Iyer. TK Govinda Rao in the back.

A Perambur Sangeetha Sabha Concert

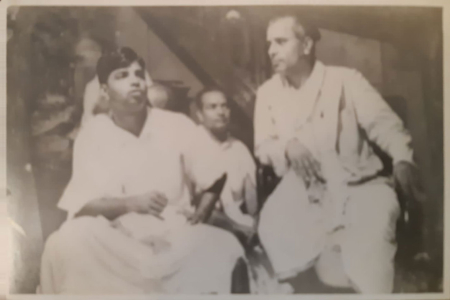

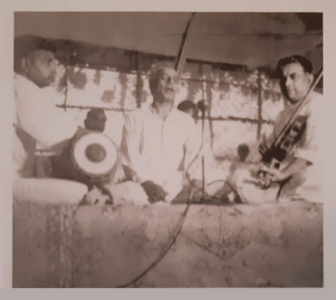

Illustration in Ananda Vikatan – Musiri with Papa Venkatramaiah and Palakad Mani Iyer. The Sishya behind is NG Seetharaman, one of his earliest disciples.

The mridanga vidwans in most of Musiri’s concerts in the early part of his career were Tanjavur Vaidyanatha Iyer and Madras Venu Naicker. Others included Pudukotai Dakshinamurthy Pillai (who played the khanjira also), Tanjavur Ramdoss Rao, Karaikudi Muthu Iyer, Palani Subramania Pillai, Palghat Mani Iyer and TK Murthy.

In 1932, Musiri embarked on a pan-India concert tour. Three years later, he toured Malaya, Burma and Ceylon to raise funds for the Ramakrishna Mission. Though he did not play an active part in the freedom movement, Musiri recorded a song for use by the Indian National Congress in elections held in the nineteen thirties. The song Udavi purivadu um kadamai stressed the duty of the public to vote for the Congress party.

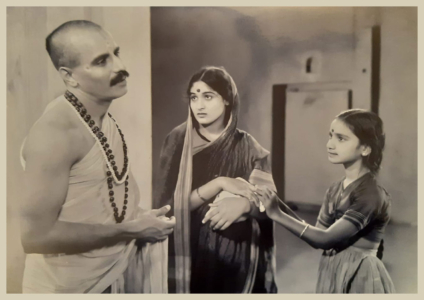

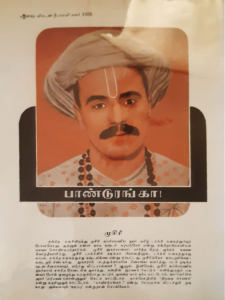

Musiri as Tukaram in the movie – 1938 Ananda Vikatan Deepavali Malar with Kalki Krishnamurthy’s comments

For the better part of his life until then, Musiri had been fighting a battle with pleurisy. His health took a downturn when he played the leading role in ‘Tukaram’, a Tamil film produced by Central Studios, perhaps because the cooler clime of Coimbatore, where the film was shot, did not agree with him. His singing as Tukaram was outstanding as was to be expected, at least four songs— Neeye paramukham, Peraanandam kaan, ]aya vithala and Syama sundara madana mohana, jey jey Panduranga—becoming runaway successes.

His musical offerings after ‘Tukaram’ tended to be chartbusters, but Musiri’s poor health forced him to cut down on his concert schedule. He actually performed from 1930 to 1945, stretching his career as long as he was able to uphold the standard he had set for himself. The day he thought his health would affect the quality of his music, he decided to gradually withdraw from the concert circuit..

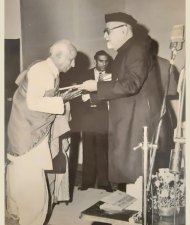

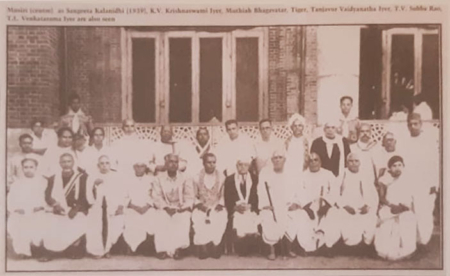

He presided over the annual conference of the Music Academy in 1939, and received on 1 January 1940 the title of Sangita Kalanidhi, one of the youngest to be so honored.

His growing stature prompted the Tyagabrahma Mahotsava Sabha in Tiruvaiyaru to persuade Musiri, in 1939, to accept the post of Secretary-Treasurer. He played a key role in uniting what was hitherto a divided house. Perhaps the leadership qualities he demonstrated at Tiruvaiyaru led to his appointment as the first principal of the Central College of Music at Madras, established by the Central Government in 1949. His musical eminence, no doubt, counted, too.

He served two terms as the head of the institution and one of its principal instructors until he retired in 1965. Many musicians associated with the college recall his splendid stewardship of it.

Musiri taught many music aspirants privately as well. His disciples included TK Govinda Rao, Mani Krishnaswamy, Suguna Purushothaman, Suguna Varadachari, and Padma Narayanaswamy. An ICS official who enrolled himself as a disciple was CV Narasimhan, later to become the UN’s under-secretary general.

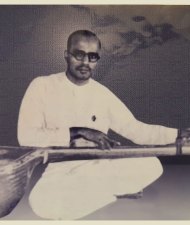

Musiri Subramania Iyer with his last batch of students. L to R : Padma Narayanswami, Rukmini Ramani, Mani Krishnaswami, and Suguna Purushothaman. On the extreme left, one sees only Suguna Varadachari”s hand!!

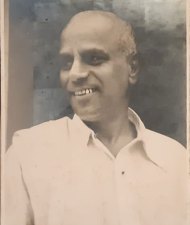

His family members adored him, especially his grandchildren. He delighted them in his forties and even later by playing with them. To his wife, he had been the typical head of the household most of his life, expecting her to produce meals and refreshments for his visitors. As they grew older, he was to become increasingly solicitous of her.

Many from the music world called on him to discuss music or play cards. He was a patient listener and spoke sparingly. His wit was subtle, sometimes sardonic.

By December 1970, Musiri’s health had deteriorated so much that he had to be admitted to the hospital, where he received news of the Presidential award of Padma Bhushan— and the doctors in the hospital joined together to present him a bouquet.

Thereafter, he mostly stayed at home.

The diplomat CV Narasimhan once told Sruti magazine:

“I fell in love with Musiri Subramania Iyer’s music at first sound. It was at my friend Rathnachalam Iyer’s house that I met Musiri for the first time. In his performance that evening, Musiri included Dikshitar’s Mukhari kriti Pahi mam Ratnachala nayaka, in honour of his host. He also sang Nagumomu at the request of the audience. It was an altogether memorable concert.

“I remember one occasion when he had just returned from Tiruvanantapuram and I heard him sing Rasa vilasa, the Swati Tirunal masterpiece in Kambhoji, just sitting in a cane chair in the front verandah, with not even a sruti box! Another memorable experience was in Kodaikanal. I attended a concert by him and heard him sing for the first time the ravishing Behag kriti, Smara janaka by Swati Tirunal.

“Pandit Ravi Shankar was Chief Producer in All India Radio Delhi, when Musiri sang in the National Programme in AIR’s auditorium on Parliament Street. His Evarani on that occasion was electrifying. Ravi Shankar said that Evarani was truly Devamritavarshini, a rain of ambrosia from heaven.”

Violin maestro TN Krishnan said this to Sruti magazine during Musiri’s centenary:

“Musiri lyerval encouraged me in many ways to become an accomplished artist and guided me properly in my career. I am very proud to say that it was through his good office that I was able to become a sishya of the great Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer. This was the turning point of my life. He was also instrumental in my joining the Central College of Carnatic Music, later known as the Tamil Nadu Government College of Music, as violin professor. I became the principal of this college later, thus following in his footsteps.

“I had the opportunity to provide him violin accompaniment in a number of concerts. Each concert was educative for me. His style was unique, full of bhava; he was a master of niraval-singing and this aspect of his music is still fresh in my mind. Also how can any music lover forget his wonderful rendering of Nagumomu, Tiruvadi saranam, Pahi Rama?

“Musiri lyerval was not only a musician with sterling qualities but also a teacher non-pareil. He was a gentleman to the core, with a subtle sense of humour.”

Grandson Thyagarajan attests to Musiri’s wit, sometimes self-deprecatory. According to Thyagu, Musiri loved telling this story at his own expense, of how he once asked for a glass of hot water experiencing some difficulty with his voice during a speech at a music-related event (he was a sought-after speaker). The lady whose help he was trying to enlist walked away, muttering, “Who does he think he is, asking for hot water? MS Subbulakshmi?”

M Krishnaswamy, of the Indian Express and husband of vocalist Mani Krishnaswamy, told Sruti magazine in 1999: “Musiri was of a serious disposition, but his comments would at times be laced with humour, probably to make me feel at ease in his presence.

“He was very good at drafting letters and liked to converse in English. In fact, I often observed Musiri and Mani, my wife who was his student, talking to each other and at times even arguing in English. Musiri was fond of reading books, driving cars, playing cards and attending horse races.

“He valued relationships. Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, MS Subbulakshmi and he, had great mutual regard. Ramnath Goenka of the Indian Express group of publications was a close friend of his.

“Despite his mastery of music, Musiri was not arrogant; he was open to ideas and suggestions. On one occasion, I heard him sing Tyagaraja’s kriti Entaniney varnintunu in Mukhari. He sang it with feeling but when he sang the first line of the charanam,

‘Kanulara sevinchi kammani phalamula nosagi’, it somehow did not convey the import of the sahitya. As my mother tongue is Telugu, I ventured to point this out to him and also explained the meaning of the line. A few days after this, he gave a concert in Tirupati in which he sang the Mukhari kriti and this time he rendered the charanam line in a different and more beautiful way. After the concert, he called me and asked me “Sariya irukka?” “Did I handle the charanam correctly?”

“He was an involved and enthusiastic teacher, a perfectionist. Most of his students were women, and he would sing in their high pitch while teaching them. He would repeat the lines loud and clear till he felt they had got it right.

“I have heard him demonstrating niraval – his niraval could melt stones, he would render it with such feeling.

“He taught not only music, but also musicianship. It was he who taught my wife Mani the essentials of concert music.

“Musiri played a vital role in my life. While he sometimes guided me in my day to day affairs, he also helped me to take some major decisions in life. It proved to be a blessing for me as well as Mani’s musical career.”

MS Subbulakshmi’s respect for Musiri was no less than her reverence for Semmangudi. Once, when MS was laid low by typhoid, Musiri visited her daily, and rendered Durusuga… the Syama Sastri masterpiece in Saveri, for her. The singer and listener both believed in the spiritual and therapeutic efficacy of great music, and this no doubt aided Subbulakshmi’s early recovery.

Can we possibly end this Musiri tribute on a more apt note? Picture the scene: A frail woman, the owner of a great voice for once reduced by illness to whispers. A man of spotless appearance singing with eyes closed, a song beseeching the goddess to bless the patient with her abundant grace. Every word is soaked in emotion, total surrender. The scene captures the man’s noble mien, his deep love of music, and his genuine empathy for those around him, better than a thousand words can. The Musiri margam. In life, as in music.

Photos from the Musiri family collection.

Dhvani thanks the Musiri Family and Sruti Magazine for their help sourcing and identifying the photos used in this article.